SIU Director’s Report - Case # 19-PFD-267

Warning:

This page contains graphic content that can shock, offend and upset.

Contents:

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information Restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (“FIPPA”)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

- Subject Officer name(s);

- Witness Officer name(s);

- Civilian Witness name(s);

- Location information;

- Witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence; and

- Other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation.

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPA”)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included. Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.Mandate Engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the death of a 48-year-old man (the “Complainant”).

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the death of a 48-year-old man (the “Complainant”).

The Investigation

Notification of the SIU

On November 12, 2019, at 8:08 p.m., the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) reported a police officer-involved shooting death to the SIU. The OPP advised it had very little information other than the deceased was still at the scene, which was being held.

At 9:21 p.m., the OPP advised that the scene was at Fifth Lake Road and County Road 14 in Stone Mills.

The Team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 3 Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 3

Complainant:

48-year-old male, deceasedCivilian Witnesses

CW #1 Interviewed CW #2 Interviewed

CW #3 Interviewed

CW #4 Interviewed

CW #5 Interviewed

CW #6 Interviewed

CW #7 Not interviewed (Next of Kin)

CW #8 Not interviewed (Next of Kin)

Witness Officers

WO #1 Interviewed WO #2 Interviewed

WO #3 Interviewed

WO #4 Interviewed

WO #5 Interviewed

Subject Officers

SO Interviewed, and notes received and reviewedEvidence

The Scene

The scene was on Fifth Lake Road, just north of County Road 14, in Stone Mills, and was protected by police barrier tape and uniformed OPP police officers. The area was rural with scattered homes and open land. County Road 14 was an east/west road. Fifth Lake Road was a north/south road and ran in a northly direction from County Road 14. Fifth Lake Road was snow-covered with packed snow. The road was narrow with ditches on each side. There was no streetlighting except for one streetlight on the northwest corner of the two roads. When viewed from County Road 14 (looking north), there was a noticeable decline in the road, followed by an incline. There were two vehicles within the protected area and they were in the low portion of the decline.

Vehicle 1:

Vehicle 2:

The body of the deceased was on the snow-covered road. He was lying parallel to the police cruiser and directly beside the driver’s door. He was on his back with his hands handcuffed behind his back. His head was towards the north and his feet were towards the south. He was wearing a brown sweater, brown jeans, and brown boots. It was apparent that emergency medical services (EMS) had attempted to resuscitate him, as his sweater had been pulled up and there were medical pads stuck to his chest and medical debris scattered around. There were visible injuries to the centre of his chest, left thigh, and left chest.

Next to the body, beside the driver's door, was a cartridge case with the headstamp WIN 9mm Luger. This was the most northerly cartridge case located. Six more cartridge cases with the same headstamp were located behind the cruiser. [An eighth cartridge case with the same headstamp was subsequently located by the OPP and provided to the SIU.] In front of the police cruiser, and between the two vehicles, was an orange-coloured aluminum baseball bat. The plastic portion of the Toyota bumper was between the two vehicles. Two marks in the roadway were marked as possible bullet strikes.

Figure 2 - The orange baseball bat located at the scene.

The Toyota was searched for weapons that would be in plain sight or within reach of the driver; no weapons were found. It appeared as if the deceased was living out of his vehicle as it was stuffed with clothing items, camping items, and old food and drink containers.

The keys to the police cruiser were obtained and the interior was photographed.

The scene was photographed showing the position of vehicles, roadway, location, and exhibits.

Scene Diagram

Forensic Evidence

Items Delivered to the Centre of Forensic Sciences (CFS)

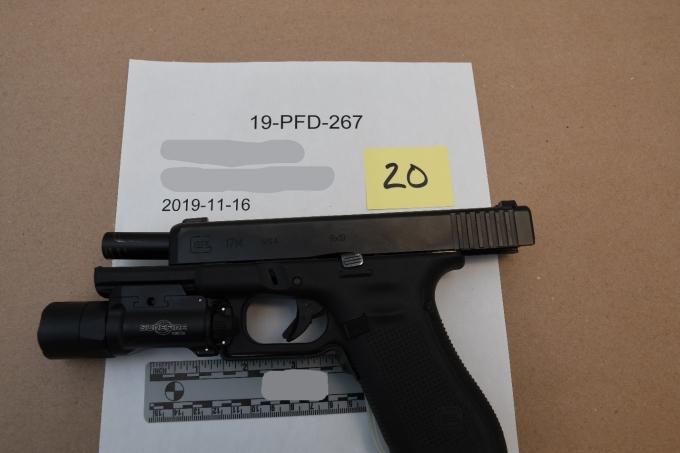

- A Glock 17M 9mm pistol and eight cartridge cases for comparison;

- Baseball bat for DNA and blood swab from the Complainant for DNA comparison;

- Brown sweater and jeans for distance determination; and

- Blood and urine for toxicology.

Examination of Baseball Bat

Examination of Gun and Cartridge Cases

Figure 3 - The SO's Glock 9mm pistol.

Communications Recordings

911 Call Communications

First 911 CallOn November 12, 2019, at 5:55:45 p.m., CW #1 called 911 and advised the call taker that a car smashed into a ditch on County Road 14. CW #1 went to see if the driver was okay, but he got snappy with him. The driver [now known to have been the Complainant] said he was staying there for the night and had guns.

The call taker asked if the Complainant was injured. CW #1 asked the Complainant and he said he was not. The Complainant opened the car door and told him to get lost. CW #1 described the car as just a small light-coloured car. CW #1 said there was an ambulance out ahead of him. He did not know if it had something to do with it.

The Complainant told him to get out of there, to leave, as he had someone coming and he had guns. The Complainant said it was dangerous territory. The call taker asked how old the Complainant appeared to be and CW #1 said older than 50 years of age by his voice. He indicated he could see the car from where he was, and the call taker asked him if he saw the Complainant leave or if someone picked him up, would he be able to call back and let them know. CW #1 replied he would.

Second 911 Call

At 6:56:21 p.m., CW #2 told the call taker that her husband, CW #1, had called an hour earlier, that there was a car in the ditch at the intersection of County Road 14 and Fifth Lake Road, and the driver said he had a gun and threatened CW #1. A police officer showed up and she heard four gunshots and her husband told her to get the kids upstairs. She did not know what was going on. The call taker asked if her husband was at the scene. She advised he was outside. He just came in and he said get the kids away and he just ran back outside.

The call taker advised that an ambulance was on scene and that CW #2 should stay inside with her children and lock the doors. The call taker asked her to stay on the phone for a few more minutes and told her that CW #1 was safe. CW #2 said her husband went to see if the driver was okay. She did not know exactly what the driver said but he basically threatened CW #1 and said he had a whole bunch of guns; that was why her husband had called the police earlier. The call taker advised that the driver of the car had been taken to hospital.

OPP Radio Communications

At 6:02:58 p.m., the dispatcher called for the SO and dispatched him to a motor vehicle collision at County Road 14; a small light-coloured car had gone into a ditch. The caller went out to check to see if they were okay. A man [now known to have been the Complainant] opened the door and told the caller to leave, that he had someone coming, he had guns, that it was dangerous territory, and that he was going to spend the night in the car. The Complainant was possibly 50 years of age. The SO acknowledged the dispatcher.

The SO asked for the address for the car in the ditch. The dispatcher asked the SO what call he was on, as his computer was lagging and he had not yet logged on. The SO called the dispatcher and said the car was in the ditch on Fifth Lake Road just north of County Road 14. The dispatcher asked the SO if he had a preference for a tow. The SO said no, just to put it on the list.

The SO called the dispatcher and said that shots were fired, he had one man injured, and to send an ambulance. The dispatcher asked the SO if he needed a second unit and he replied he did. The SO said he was all good there. After a few minutes, he said the Complainant had multiple gunshot wounds and he had started CPR. The dispatcher advised the ambulance was rolling, they were near Church Road, and they were just a few minutes out.

Approximately four minutes later, the SO said the ambulance was on scene. The dispatcher advised he was on the phone with WO #4, who was on his way and he wanted WO #3 to secure the scene. WO #4 wanted the SO to go with the Complainant in the ambulance.

The SO advised he was doing CPR. He said he was okay and that the Complainant was unresponsive. CPR was being continued with the SO, a volunteer firefighter, and paramedics. The SO advised that the Complainant was pronounced dead at 7:05 p.m.

WO #2 advised he was on scene and everything was under control. The SO was okay. They had a crime scene situation right now. WO #4 asked WO #2 or WO #3 to take a statement from CW #1, in writing, and the other to keep scene continuity, until he arrived. WO #2 advised the dispatcher that the SO was with him in his police cruiser and they were departing the scene and going to the Napanee Detachment.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the OPP:- Intergraph Computer-Assisted Dispatch (CAD)-Event Details;

- OPP audio statement-CW #1.;

- Notes of the witness officers and the SO

- Occurrence Details Report;

- 911 Calls recordings;

- OPP radio communications recordings;

- OPP Police Orders-Law Enforcement;

- OPP Police Orders- Tactic and Rescue Unit team mandate;

- OPP Police Orders-Provincial Communications Centre Standard Operating Procedure Manual; and

- Training Records-the SO.

Materials obtained from Other Sources

Investigators also obtained and reviewed the following materials from other sources:- EMS Incident Report;

- Ambulance Call Report;

- Fire Department - CAD;

- Notes of five firefighters; and

- CFS Biology Report.

Incident Narrative

The evidence of the material events surrounding the shooting is uncontested. It includes interviews with the SO, and an additional five police and six civilian witnesses. The investigation also benefitted from a review of the police communications recordings, forensic examination of the scene and items of evidence, and the post-mortem examination.

Shortly before 6:00 p.m. on November 12, 2019, a Toyota motor vehicle operated by the Complainant was involved in a single vehicle collision, with the vehicle ending up in the ditch on the east side of County Road 14, just north of Fifth Lake Road, in Stone Mills. CW #1 approached the motor vehicle and inquired if the driver, the Complainant, was injured. After some conversation, the Complainant told CW #1 that he had guns in the car, he knew dangerous people, and there was someone coming to get him. CW #1 called 911, advising them of the crash and the Complainant’s comment that he had guns in the car.

The SO, who was working alone at the time, was dispatched to the area. Following the initial dispatch, the SO was only aware that there had been a crash; he was unaware of the threat of firearms in the car even though that information appears to have been broadcasted by the dispatcher. While en route to the crash location, the SO had the opportunity to read the information updated on his in-car-computer and learned of the threat of guns in the crashed vehicle; however, because it was hunting season and the area was a rural one, the presence of firearms in a motor vehicle was not necessarily unusual.

Upon the SO’s arrival at the scene, he approached the Complainant, who was still seated in his car, and they had some conversation. The Complainant advised the SO that he was fine and would spend the night in his car, as he was homeless. The SO suggested an alternate plan to the Complainant wherein he would arrange for the vehicle to be towed and the Complainant could spend the night at a shelter. The Complainant accepted the plan and the SO returned to his police vehicle, called for a tow truck, and checked the Complainant’s background with the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC). The information that came back indicated that the Complainant was flagged for violence and prohibited from possessing any firearms.

As a result of the CPIC check, the SO again approached the Complainant and positioned himself a short distance from the driver’s door. The officer advised the Complainant that he, the Complainant, had indicated to CW #1 that he had firearms in his vehicle, despite the fact he was prohibited from possessing any firearms. The Complainant denied having any firearms in his vehicle, while simultaneously becoming visibly agitated, sitting up, shifting his weight, and glaring towards the SO. At this time, the SO observed an aluminum bat propped up on the front passenger seat; he had not observed the bat prior to his returning to his police cruiser. Suddenly, the Complainant grabbed the neck of the baseball bat and gripped it tightly with his right hand, while indicating that this was his protection. He then began to exit the car with the bat in hand, while the SO ran out of the ditch and onto the roadway in order to distance himself from the Complainant. The Complainant stood in the ditch, with both hands gripped tightly around the neck of the bat as he moved it up and down above his shoulder. The SO, in fear of being injured or killed, commanded the Complainant not to move and to drop the bat. Independent evidence confirmed that the SO shouted, “Put it down! Put it down!”

The Complainant began to walk up and out of the ditch as the SO continued to command him to drop the bat. The Complainant responded that the SO would have to shoot him, at which point he first walked, and then began a slow jog, directly at the officer. The SO continued to retreat, eventually moving behind the front of his police vehicle and using it as cover, while continuing to command that the Complainant drop the bat; there was no other cover available and the SO had nowhere else to go. The officer had his firearm out at this time and pointed at the Complainant. The Complainant rounded the front of the police cruiser and began to run toward the SO, who then discharged his firearm at the Complainant. After discharging his firearm twice, and striking the Complainant, the Complainant did not slow but continued to move toward the SO, at which point the SO fired a second volley of shots at the Complainant, who then fell to the ground, still gripping the bat. The time was about 6:53 p.m.

The SO immediately moved in to where the Complainant had fallen, kicked the bat away, and began life saving measures on the Complainant. Paramedics and firefighters soon arrived and took over the Complainant’s care. The Complainant was pronounced dead at the scene at 7:05 p.m.

A later examination of the scene revealed a bat lying on the ground between the Toyota and the police cruiser, as well as eight cartridge cases. The baseball bat was examined by the CFS and it was determined with near certainty that the DNA on the bat belonged to the Complainant.

Cause of Death

The post-mortem examination determined that the cause of the Complainant’s death was “gunshot wound of torso.” Four entrance gunshot wounds were located in the left thigh of the Complainant, with four exit wounds to the back of his left leg, below the buttocks. A gunshot wound was also located in the Complainant’s upper arm with a probable re-entry into the left chest. A small piece of copper jacket was located in the Complainant’s arm and a bullet core was recovered from his left chest area. A gunshot wound was also located in the chest, with the projectile located in the right lower back.

Shortly before 6:00 p.m. on November 12, 2019, a Toyota motor vehicle operated by the Complainant was involved in a single vehicle collision, with the vehicle ending up in the ditch on the east side of County Road 14, just north of Fifth Lake Road, in Stone Mills. CW #1 approached the motor vehicle and inquired if the driver, the Complainant, was injured. After some conversation, the Complainant told CW #1 that he had guns in the car, he knew dangerous people, and there was someone coming to get him. CW #1 called 911, advising them of the crash and the Complainant’s comment that he had guns in the car.

The SO, who was working alone at the time, was dispatched to the area. Following the initial dispatch, the SO was only aware that there had been a crash; he was unaware of the threat of firearms in the car even though that information appears to have been broadcasted by the dispatcher. While en route to the crash location, the SO had the opportunity to read the information updated on his in-car-computer and learned of the threat of guns in the crashed vehicle; however, because it was hunting season and the area was a rural one, the presence of firearms in a motor vehicle was not necessarily unusual.

Upon the SO’s arrival at the scene, he approached the Complainant, who was still seated in his car, and they had some conversation. The Complainant advised the SO that he was fine and would spend the night in his car, as he was homeless. The SO suggested an alternate plan to the Complainant wherein he would arrange for the vehicle to be towed and the Complainant could spend the night at a shelter. The Complainant accepted the plan and the SO returned to his police vehicle, called for a tow truck, and checked the Complainant’s background with the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC). The information that came back indicated that the Complainant was flagged for violence and prohibited from possessing any firearms.

As a result of the CPIC check, the SO again approached the Complainant and positioned himself a short distance from the driver’s door. The officer advised the Complainant that he, the Complainant, had indicated to CW #1 that he had firearms in his vehicle, despite the fact he was prohibited from possessing any firearms. The Complainant denied having any firearms in his vehicle, while simultaneously becoming visibly agitated, sitting up, shifting his weight, and glaring towards the SO. At this time, the SO observed an aluminum bat propped up on the front passenger seat; he had not observed the bat prior to his returning to his police cruiser. Suddenly, the Complainant grabbed the neck of the baseball bat and gripped it tightly with his right hand, while indicating that this was his protection. He then began to exit the car with the bat in hand, while the SO ran out of the ditch and onto the roadway in order to distance himself from the Complainant. The Complainant stood in the ditch, with both hands gripped tightly around the neck of the bat as he moved it up and down above his shoulder. The SO, in fear of being injured or killed, commanded the Complainant not to move and to drop the bat. Independent evidence confirmed that the SO shouted, “Put it down! Put it down!”

The Complainant began to walk up and out of the ditch as the SO continued to command him to drop the bat. The Complainant responded that the SO would have to shoot him, at which point he first walked, and then began a slow jog, directly at the officer. The SO continued to retreat, eventually moving behind the front of his police vehicle and using it as cover, while continuing to command that the Complainant drop the bat; there was no other cover available and the SO had nowhere else to go. The officer had his firearm out at this time and pointed at the Complainant. The Complainant rounded the front of the police cruiser and began to run toward the SO, who then discharged his firearm at the Complainant. After discharging his firearm twice, and striking the Complainant, the Complainant did not slow but continued to move toward the SO, at which point the SO fired a second volley of shots at the Complainant, who then fell to the ground, still gripping the bat. The time was about 6:53 p.m.

The SO immediately moved in to where the Complainant had fallen, kicked the bat away, and began life saving measures on the Complainant. Paramedics and firefighters soon arrived and took over the Complainant’s care. The Complainant was pronounced dead at the scene at 7:05 p.m.

A later examination of the scene revealed a bat lying on the ground between the Toyota and the police cruiser, as well as eight cartridge cases. The baseball bat was examined by the CFS and it was determined with near certainty that the DNA on the bat belonged to the Complainant.

Cause of Death

Relevant Legislation

Section 25, Criminal Code -- Protection of persons acting under authority

25 (1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law

(a) as a private person,(b) as a peace officer or public officer,(c) in aid of a peace officer or public officer, or(d) by virtue of his office,

is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose.

25 (3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservations of any one under that person’s protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

Section 34, Criminal Code -- Defence of person - Use of threat of force

34 (1) A person is not guilty of an offence if

(a) They believe on reasonable grounds that force is being used against them or another person or that a threat of force is being made against them or another person;(b) The act that constitutes the offence is committed for the purpose of defending or protecting themselves or the other person from that use or threat of force; and(c) The act committed is reasonable in the circumstances.

(2) In determining whether the act committed is reasonable in the circumstances, the court shall consider the relevant circumstances of the person, the other parties and the act, including, but not limited to, the following factors:

(a) the nature of the force or threat;(b) the extent to which the use of force was imminent and whether there were other means available to respond to the potential use of force;(c) the person’s role in the incident;(d) whether any party to the incident used or threatened to use a weapon;(e) the size, age, gender and physical capabilities of the parties to the incident;(f) the nature, duration and history of any relationship between the parties to the incident, including any prior use or threat of force and the nature of that force or threat;(f.1) any history of interaction or communication between the parties to the incident;(g) the nature and proportionality of the person’s response to the use or threat of force; and(h) whether the act committed was in response to a use or threat of force that the person knew was lawful.

Analysis and Director's Decision

In the evening of November 12, 2019, the Complainant was shot multiple times by the SO in the Township of Stone Mills, resulting in his death. On my assessment of the evidence, there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the SO committed a criminal offence in connection with the Complainant’s death.

Whether considered pursuant to the frameworks set out in section 25(3) or 34 of the Criminal Code, the first setting out the test for legal justification in the case of lethal force used in the execution of a police officer’s duty, the other outlining the parameters of force that is excusable in defence of oneself or another, I am satisfied on reasonable grounds that the SO’s conduct did not run afoul of the limits prescribed by the criminal law. The Complainant, with a potentially lethal weapon in hand, chose to run at the SO. The SO, on the other hand, continually moved back and away from the Complainant, initially getting out of the ditch and onto the roadway and then, when the Complainant continued to advance on the SO, moving behind his police cruiser for cover. Throughout the Complainant’s advance on the SO, the SO continually directed the Complainant to stop and drop his weapon. Finally, when the SO had no place else to go, he discharged his firearm at the advancing Complainant. One or both of the first volley of two shots struck the Complainant but failed to incapacitate him. He kept moving toward the officer wielding the bat in a threatening fashion as the officer let off a second volley of gunfire consisting of six shots.

The SO, in his interview with SIU investigators, indicated that he fired his weapon fearing for his life and that he acted pursuant to his training when dealing with an armed attacker.

On the aforementioned record, I accept that the SO genuinely and reasonably believed that shooting the Complainant was necessary to protect himself from loss of life or grievous bodily harm. The officer was confronted by an individual threatening him with a dangerous weapon at close range. While the officer continually retreated from the Complainant, and attempted to take cover behind his police vehicle, when the Complainant continued to advance on him, he left the SO with no other options for a safe retreat. The SO found himself alone, without backup, and facing an armed attacker with no recourse for further retreat. By the time the Complainant had moved around the police cruiser to the side where the SO had sought refuge, the Complainant was placing himself within striking range of the SO, who then decided to discharge his weapon. The SO had a difficult decision to make and split seconds in which to make it. In the circumstances, I am satisfied on reasonable grounds that the SO was within his rights in choosing to fire his firearm at the Complainant.

It should be noted that the SO was in possession of a CEW at the time, raising the question of its potential use to neutralize the threat posed by the Complainant. By the time the Complainant emerged from his vehicle wielding a bat menacingly at the SO, the threat confronting the officer had instantly become potentially lethal in nature. Moreover, the SO did not have the benefit of a partner with him, in which scenario one or the other officer could have drawn their CEW while the other unholstered their firearm. In the circumstances, I am unable to fault the SO for not first resorting to his CEW given the threat level and the speed with which events unfolded. Nor do I believe that the number of shots fired by the SO makes any difference in the liability analysis. While the Complainant appears to have been struck by one or more of the first two shots, he was not felled by either of them and continued to advance toward the officer bat in hand. With respect to the second volley of six shots, I am unable to infer any material difference in the threat level the SO would have reasonably apprehended across shots three through eight given the rapid succession of the gunfire and the volatility of the situation. In arriving at this conclusion, I have in mind the common law principle that officers caught up in violent encounters are not expected to measure their countervailing force with precision; what is required is a reasonable response, not an exacting one: R. v. Nasogaluak, [2010] 1 SCR 206; R. v. Baxter (1975), 27 CCC (2d) 96 (Ont. C.A.).

Date: April 27, 2020

Electronically approved by

Joseph Martino

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Whether considered pursuant to the frameworks set out in section 25(3) or 34 of the Criminal Code, the first setting out the test for legal justification in the case of lethal force used in the execution of a police officer’s duty, the other outlining the parameters of force that is excusable in defence of oneself or another, I am satisfied on reasonable grounds that the SO’s conduct did not run afoul of the limits prescribed by the criminal law. The Complainant, with a potentially lethal weapon in hand, chose to run at the SO. The SO, on the other hand, continually moved back and away from the Complainant, initially getting out of the ditch and onto the roadway and then, when the Complainant continued to advance on the SO, moving behind his police cruiser for cover. Throughout the Complainant’s advance on the SO, the SO continually directed the Complainant to stop and drop his weapon. Finally, when the SO had no place else to go, he discharged his firearm at the advancing Complainant. One or both of the first volley of two shots struck the Complainant but failed to incapacitate him. He kept moving toward the officer wielding the bat in a threatening fashion as the officer let off a second volley of gunfire consisting of six shots.

The SO, in his interview with SIU investigators, indicated that he fired his weapon fearing for his life and that he acted pursuant to his training when dealing with an armed attacker.

On the aforementioned record, I accept that the SO genuinely and reasonably believed that shooting the Complainant was necessary to protect himself from loss of life or grievous bodily harm. The officer was confronted by an individual threatening him with a dangerous weapon at close range. While the officer continually retreated from the Complainant, and attempted to take cover behind his police vehicle, when the Complainant continued to advance on him, he left the SO with no other options for a safe retreat. The SO found himself alone, without backup, and facing an armed attacker with no recourse for further retreat. By the time the Complainant had moved around the police cruiser to the side where the SO had sought refuge, the Complainant was placing himself within striking range of the SO, who then decided to discharge his weapon. The SO had a difficult decision to make and split seconds in which to make it. In the circumstances, I am satisfied on reasonable grounds that the SO was within his rights in choosing to fire his firearm at the Complainant.

It should be noted that the SO was in possession of a CEW at the time, raising the question of its potential use to neutralize the threat posed by the Complainant. By the time the Complainant emerged from his vehicle wielding a bat menacingly at the SO, the threat confronting the officer had instantly become potentially lethal in nature. Moreover, the SO did not have the benefit of a partner with him, in which scenario one or the other officer could have drawn their CEW while the other unholstered their firearm. In the circumstances, I am unable to fault the SO for not first resorting to his CEW given the threat level and the speed with which events unfolded. Nor do I believe that the number of shots fired by the SO makes any difference in the liability analysis. While the Complainant appears to have been struck by one or more of the first two shots, he was not felled by either of them and continued to advance toward the officer bat in hand. With respect to the second volley of six shots, I am unable to infer any material difference in the threat level the SO would have reasonably apprehended across shots three through eight given the rapid succession of the gunfire and the volatility of the situation. In arriving at this conclusion, I have in mind the common law principle that officers caught up in violent encounters are not expected to measure their countervailing force with precision; what is required is a reasonable response, not an exacting one: R. v. Nasogaluak, [2010] 1 SCR 206; R. v. Baxter (1975), 27 CCC (2d) 96 (Ont. C.A.).

Date: April 27, 2020

Electronically approved by

Joseph Martino

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Note:

The signed English original report is authoritative, and any discrepancy between that report and the French and English online versions should be resolved in favour of the original English report.